C

Pointers¶

Reference Operator¶

In expressions * derefences a pointer, (and does other jobs as per grammar).

In declarations * marks a variable as a pointer.

1 | |

a

1 | |

int as input. But makes a copy of the pointer.

Important

The rule of declaration in C is, you declare it the way you use it.

Example

int *p means you need *p (a pointer) to get a int

int **p means you need **p (a pointer to a pointer) to get a int

int ***p means you need ***p (a pointer to a pointer to a pointer) to get a int

| Little Examples of Pointers | |

|---|---|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 | |

value: 1

pointer: 1

pointer to pointer: 1

pointer to pointer to pointer: 1

Address Operator¶

In expressions & gets you the address of a pointer.

Constant Pointers¶

Consider the following example,

1 | |

ptr points to a which is of const int type. What that means is that the value of a is read-only; however that does not mean the pointer is read-only: the reference that ptr holds can be changed at any time,

1 | |

However if a constant pointer is declared, its value cannot be changed:

1 | |

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 | |

./main

ptr: 69

ptr: 420

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 | |

main.c:9:6: error: cannot assign to variable 'ptr' with const-qualified type 'const int *const'

9 | ptr = &b;

| ~~~ ^

main.c:6:19: note: variable 'ptr' declared const here

6 | const int *const ptr = &a;

| ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~^~~~~~~~

1 error generated.

As you can see, a constant pointer's value cannot be changed.

Arithmetic¶

Important

When you increment a pointer of any type by n, it increments the pointer by the size of its type times n.

Simple¶

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 | |

./main

sizeof(int): 4

Address of p: 140721500910884

n1: 140721500910888

n2: 140721500910892

Difference: 4, 4

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 | |

./main

sizeof(int): 4

Address of p: 140721262450916

n1: 140721262450928

n2: 140721262450940

Difference: 12, 24

4 * 3 = 12, 4 * 6 = 24

Arrays¶

Since arrays are contiguous in memory, you can do quite a bit of sophisticated array manipulation using pointer arithmetic.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 | |

./main

1

2

3

4

5

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 | |

./main

1

2

3

4

5

Note

*(p+n) is equivalent to p[n]. The latter is a syntactic sugar for the former.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 | |

./main

0x7ffd9a93ad90 1

0x7ffd9a93ad94 2

0x7ffd9a93ad98 3

0x7ffd9a93ad9c 4

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 | |

./main

Test

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 | |

./main

69

Pointers in Structs¶

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 | |

- Since

nameis an array, when you pass it to the constructor, the compiler passes a pointer to the first element of the array. If the struct wasn't accepting a pointer to an array of array of 50chars, but instead accepted a pointer to an array of 50chars then you would acceptconst char* imagein the struct definition, for the same reason I just stated.

./main

height: 1080, width: 720, name: Hello!

height: 1080, width: 720, name: Hello!

height: 1080, width: 720, name: Hello!

height: 1080, width: 720, name: Hello!

Function Pointers¶

You declare function pointers with the following syntax:

<return type> (*<pointer_name>)(<argument type>, ...);

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 | |

./main

Sum of 1 + 2 is 3

Dynamic Memory¶

malloc, calloc, realloc, free, are available in stdlib.h.

1 2 3 4 | |

-

calloc()allocates memory for an array ofnmembelements of size bytes each and returns a pointer to the allo- cated memory. The memory is set to zero. -

malloc()allocates size bytes and returns a pointer to the allocated memory. The memory is not cleared. -

free()frees the memory space pointed to byptr, which must have been returned by a previous call tomalloc(),calloc()orrealloc(). Otherwise, or iffree(ptr)has already been called before, undefined behaviour occurs. IfptrisNULL, no operation is performed. -

realloc()changes the size of the memory block pointed to byptrto size bytes. The contents will be unchanged to the minimum of the old and new sizes; newly allocated memory will be uninitialized. IfptrisNULL, the call is equivalent tomalloc(size); if size is equal to zero, the call is equivalent tofree(ptr). UnlessptrisNULL, it must have been returned by an earlier call tomalloc(),calloc()orrealloc().

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 | |

print_pointer will only print "allocated", but with the second

call the behaviour is undefined.

./main

[PROMPT] Enter text size in bytes: 5

[INFO] Entered bytes: 5

pointer: 0

pointer: 0

pointer: 0

pointer: 0

pointer: 0

[INFO] Memory free'd.

pointer: -92

pointer: 17

pointer: 0

pointer: 0

pointer: 0

Important

1 | |

1 | |

p and a are not equivalent. The first example requests a contiguous

block of memory of size N * sizeof(int) then names it a, however a is not a

pointer, it is an array. But the second example only assigns a reference to a contiguous

block of memory to a pointer (p). When you pass a to a function the compiler instead

passes a pointer to the first element of the array, but when you pass p to a function,

it just passes itself. If a function happens to change the reference in the pointer p,

the contiguous block of memory that it holds reference to is now forever lost. But in

case of a, the original array is never lost since a is not a pointer by itself, it

is the compiler that does the magic when you pass the array a to a function.

Important

Calling free() on a pointer doesn't change it, only marks memory as free. Your

pointer will still point to the same location which will contain the same value, but

that value can now get overwritten at any time, so you should never use a pointer after

it is free'd. To ensure that, it is a good idea to always set the pointer to NULL

after free'ing it.

Memory Leaks¶

Consider the following example,

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 | |

N=30, then we assign random values to the pointers.

We then allocate N*2 bytes to B pointer. We then overwrite the reference value in

variable B with A's reference value. Now the dynamic memory block's reference we got

from malloc at line 12 is lost. This loss of bytes is termed as a memory leak.

Tip

See this forum post to find memory leaks in your program.

Copying Memory¶

- The

memcpy()function copiesnbytes from memory areasrcto memory areadest. The memory areas must not overlap. - The

memmove()function copiesnbytes from memory areasrcto memory areadest. The memory areas may overlap: copying takes place as though the bytes insrcare first copied into a temporary array that does not overlapsrcordest, and the bytes are then copied from the temporary array todest.1 2

void *memcpy(void *dest, const void *src, size_t n); void *memmove(void *dest, const void *src, size_t n);memcpy()andmemmove()are declared instring.h.memcpy()does not support overlapping butmemmove()does. That's the difference between the two. Otherwise they are equivalent. Look and understand the example below and then study the output.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 | |

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 | |

Stack and Heap¶

Stack¶

Areas of memory of a program are called segments: the text segment, the stack segment, and the heap segment.

- The text (or code) segment contains the compiled code of the executable.

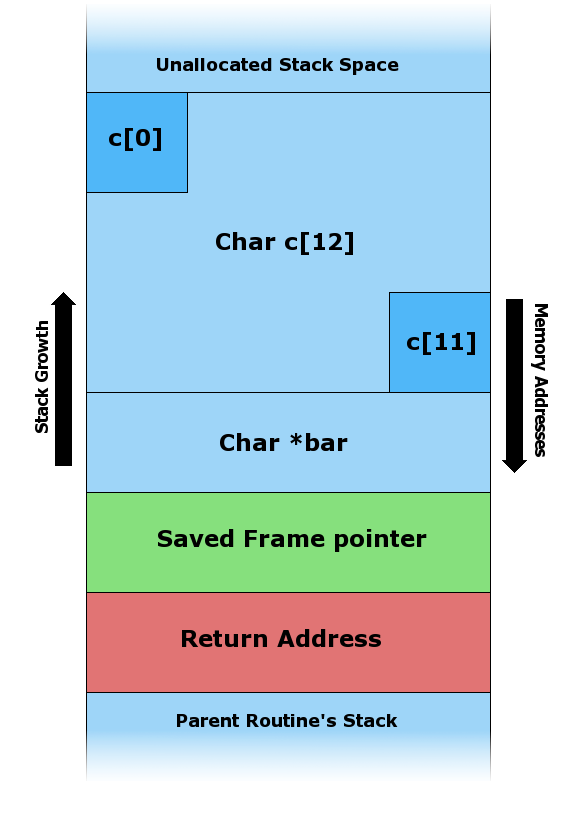

- The stack segment is used to store your local variables and is used for passing arguments to the functions along with the return address of the instruction which is to be executed after the function call is over. When a new stack frame needs to be added (as a result of a newly called function), the stack grows downward.

- The heap segment is used when program allocate memory at runtime using

callocandmallocfunction, then memory gets allocated in heap. When some more memory need to be allocated usingcallocandmallocfunction, heap grows upward as shown in above diagram.

The stack and heap are traditionally located at opposite ends of the process’s virtual

address space. The stack grows automatically when accessed, up to a size set by the

kernel (which can be adjusted with setrlimit(RLIMIT_STACK, ...) on UNIX systems). The

heap grows when the memory allocator invokes the brk() or sbrk() system call,

mapping more pages of physical memory into the process’s virtual address space.

Implementation of both the stack and heap is usually down to the runtime/OS. Often games and other applications that are performance critical create their own memory solutions that grab a large chunk of memory from the heap and then dish it out internally to avoid relying on the OS for memory

Stacks in computing architectures are regions of memory where data is added or removed in a last-in-first-out manner. In most modern computer systems, each thread has a reserved region of memory referred to as its stack. When a function executes, it may add some of its state data to the top of the stack; when the function exits it is responsible for removing that data from the stack. At a minimum, a thread’s stack is used to store the location of function calls in order to allow return statements to return to the correct location, but programmers may further choose to explicitly use the stack. If a region of memory lies on the thread’s stack, that memory is said to have been allocated on the stack.

Because the data is added and removed in a last-in-first-out manner, stack allocation is very simple and typically faster than heap-based memory allocation (also known as dynamic memory allocation). Another feature is that memory on the stack is automatically, and very efficiently, reclaimed when the function exits.

Important

Do not return pointers to static variables from a function's scope. Static variables are

automatically free'd outside the function's scope.

Tip

For a simplified introduction to stack and heap read this and for more detailed introduction read this.

- The OS allocates the stack for each system-level thread when the thread is created. Typically the OS is called by the language runtime to allocate the heap for the application.

- The stack is attached to a thread, so when the thread exits the stack is reclaimed. The heap is typically allocated at application startup by the runtime, and is reclaimed when the application (technically process) exits.

- The size of the stack is set when a thread is created.

- You would use the stack if you know exactly how much data you need to allocate before compile time and it is not too big.

- The stack is faster because the access pattern makes it trivial to allocate memory from it, while the heap has much more complex bookkeeping involved in an allocation or free. Also, each byte in the stack tends to be reused very frequently which means it tends to be mapped to the processor’s cache, making it very fast.

- Variables created on the stack will go out of scope and automatically deallocate.

- Much faster to allocate in comparison to variables on the heap.

- Implemented with an actual stack data structure.

- Stores local data, return addresses, used for parameter passing

- Can have a stack overflow when too much of the stack is used. (mostly from inifinite or too much recursion and very large allocations)

- Data created on the stack can be used without pointers.

- In C you can get the benefit of variable length allocation through the use of

alloca(), which allocates on the stack, as opposed to alloc, which allocates on the heap. This memory won’t survive your return statement, but it’s useful for a scratch buffer.

Stack Overflow¶

Variables created on the stack are always contiguous with each other, writing out of bounds can change the value of another variable.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 | |

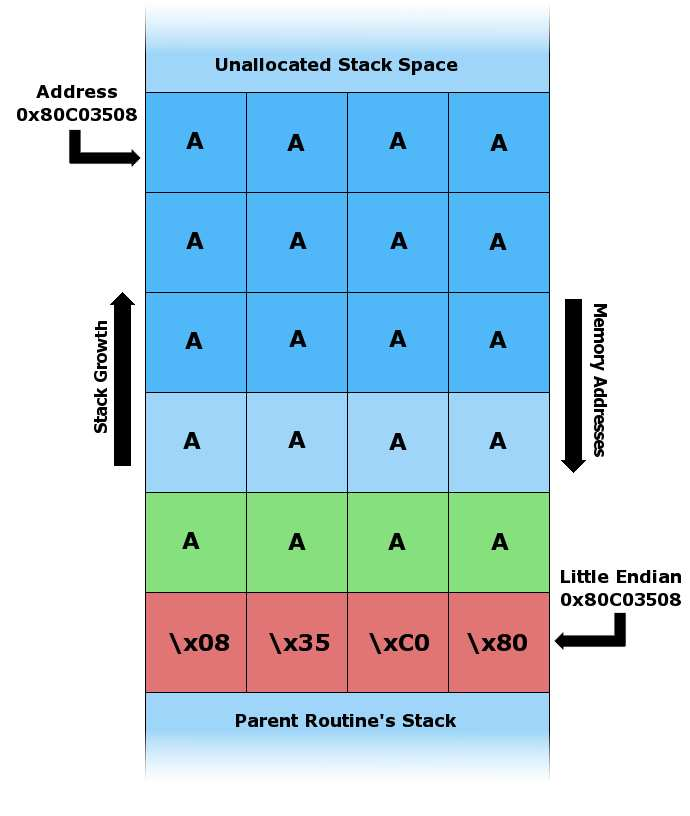

foo() overwrites

local stack data, the saved frame pointer, and most importantly, the return address.

When foo() returns it pops the return address off the stack and jumps to that address

(i.e. starts executing instructions from that address). In the example above,

the attacker has overwritten the return address with a pointer to the stack

buffer char c[12], which now contains attacker supplied data. In an actual stack

buffer overflow exploit the string of ”A”’s would be replaced with

shellcode suitable to the platform.

Heap¶

The heap contains a linked list of used and free blocks. New allocations on the heap (by

new (C++) or malloc()) are satisfied by creating a suitable block from one of the

free blocks. This requires updating list of blocks on the heap. This meta information

about the blocks on the heap is also stored on the heap often in a small area just in

front of every block.

- The size of the heap is set on application startup, but can grow as space is needed (the allocator requests more memory from the operating system).

- Stored in computer RAM like the stack.

- Variables on the heap must be destroyed manually and never fall out of scope. The data is freed with delete, delete[] or free

- Slower to allocate in comparison to variables on the stack.

- Used on demand to allocate a block of data for use by the program.

- Can have fragmentation when there are a lot of allocations and deallocations

- Can have allocation failures if too big of a buffer is requested to be allocated.

- You would use the heap if you don’t know exactly how much data you will need at runtime or if you need to allocate a lot of data.

- Responsible for memory leaks.

Heap Overflow¶

A heap overflow, heap overrun, or heap smashing is a type of buffer overflow that occurs

in the heap data area. Heap overflows are exploitable in a different manner to that of

stack-based overflows. Memory on the heap is dynamically allocated at runtime and

typically contains program data. Exploitation is performed by corrupting this data in

specific ways to cause the application to overwrite internal structures such as linked

list pointers. The canonical heap overflow technique overwrites dynamic memory

allocation linkage (such as malloc metadata) and uses the resulting pointer exchange

to overwrite a program function pointer.

Tip

Read more here.

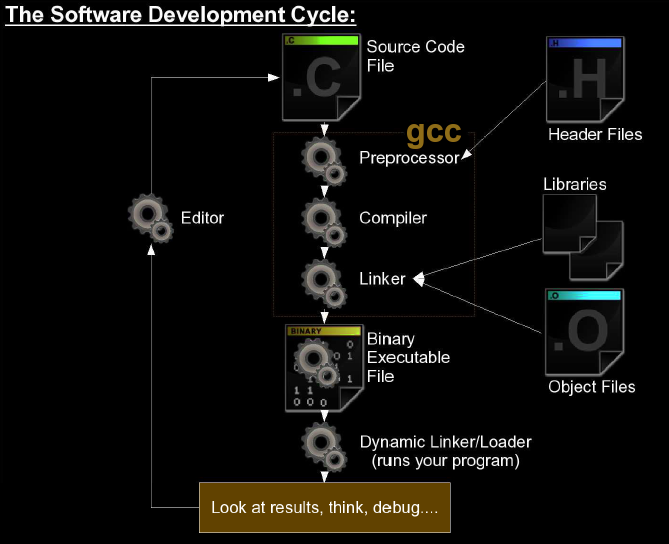

Compilation¶

Libraries are archives of object files. In a

sense object files are simply compiled byte code of your source code that is yet to be

linked. Before linking your source code went through several stages, those stages as part of

their process ensure your linker can do its job correctly and efficiently. Before linking

your compiler only makes reference to things like external functions like printf. A

linker's job is to actually look for them and... Link them to your program.

Once the linker is done with its job, it outputs an executable that you can run on a specific CPU architecture.

Note

Inclusion of source code into another file using #include, #define, etc.,

and making sure it actually exists is not the job of the linker. That's the job of the

preprocessor. E.g., if your source code is missing the definition of a

variable, the error is from the preprocessor, not the linker.

gcc -c main.c

main.o.

gcc -S main.c

main.s.

gcc -o main.c

main.

Libraries¶

As explained, libraries are archives of object files.

Making and Using Static Libraries¶

For a bare-minimum example, you will need two files, test.h and test.o, to create the

static library. test.h is needed for the program that is to make use of your library; without

it the preprocessor will not be able to make sense of your use of symbols that are

undeclared from the preprocessor's perspective (not the linker).

To create the static library we will use ar

that is available on Unix and Unix-like systems. This command is simply an archiver.

ar -csr libtest.a test.o

-ccreate the library if it doesn't exist.-sgenerate an index.-rreplace anything of the same name that is already in the library.

Tip

You can view the manpage for more information, man ar.

Tip

You can view the filenames of the object files that are in an archive with

ar -t libname.[a,so].

Note

gcc lets you add other directories onto the linker's

search path by defining the environment variable LIBRARY_PATH. Just

put a colon-separated list of directories into this variable, and gcc

will add these directories to the standard list of places where it

looks for static libraries.

A library must be prefixed with lib. A static library must end with .a extension.

Between lib and .a is the name of your library.

gcc -o main -L. -ltest main.c

-Ltellsgccto look in an additional directory when trying to find libraries.-Itellsgccto look in an additional directory when trying to findincludefiles.-lsays to link the program with the following library.testis the name of the library.

1 | |

1 2 3 4 5 | |

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | |

./main

3

Making and Using Dynamic Libraries¶

Please read the Creating and Using Dynamic Libraries section from here.

Type Qualifiers¶

Tip

Refer to this article

for more information on const and volatile.

const (C89)¶

const is used with a datatype declaration or definition to specify an unchanging value.

1 2 | |

const objects may not be changed.

| Illegal Uses of Const | |

|---|---|

1 2 3 4 5 | |

volatile (C89)¶

volatile specifies a variable whose value may be changed by processes outside the current program

| Volatile Object That Might Be a Buffer Used to Exchange Data With an External Device | |

|---|---|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 | |

iobuf had not been declared volatile, the compiler would notice that nothing happens inside the loop and thus eliminate the loop

const and volatile can be used together.

Note

An input-only buffer for an external device could be declared as const volatile (or volatile const, order is not important) to make sure the compiler knows that the variable should not be changed (because it is input-only) and that its value may be altered by processes other than the current program

restrict (C99)¶

restrict keyword hints the compiler no other pointer can be used to point to the

object that a pointer with this type qualifier points to.

Tip

Read this page for more inforamtion.

_Atomic (C11)¶

Their purpose is to ensure race-free access to variables that are shared between different threads. Without atomic qualification, the state of a shared variable would be undefined if two threads access it concurrently.

Note

For more information please refer to this answer.

| Atomic Constant Integer Variable Declaration | |

|---|---|

1 | |

Tip

Read about data races here.

Storage Classes¶

Tip

Refer to this page for more information. You can also find more information on this thread.

auto¶

auto is the default storage class for all local variables. Automatic, or local, or stack variables only last for its scope's lifetime.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 | |

./main

ptr: 69

ptr: 1957747793

static (Internal Linkage)¶

The static storage class instructs the compiler to keep a local variable in existence

during the life-time of the program instead of creating and destroying it each time it

comes into and goes out of scope. Therefore, making local variables static allows them

to maintain their values between function calls.

Note

static variables are by default initiliazed to zero. Non-static variables may also be

zero but you are entirely dependent on the compiler's implementation (undefined behavior).

Note

When static is explicitly used for declaring a global variable (or function), it causes that

variable's scope to be restricted to the file in which it is declared.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 | |

./main

ptr: 69

ptr: 69

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 | |

./main

i is 6 and count is 9

i is 7 and count is 8

i is 8 and count is 7

i is 9 and count is 6

i is 10 and count is 5

i is 11 and count is 4

i is 12 and count is 3

i is 13 and count is 2

i is 14 and count is 1

i is 15 and count is 0

extern (External Linkage)¶

The extern storage class is used to give a reference of a global variable that is

visible to ALL the program files. When you use extern the variable cannot be

initialized as all it does is point the variable name at a storage location that has

been previously defined.

Inforamtion

When global variables (or functions) are declared, unless specified, they are classified with external linkage.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 | |

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | |

> gcc support.c main.c -o main

> ./main

5

register¶

register keyword is used to suggest the compiler to put the variable in a CPU

register. Since CPU registers is the fastest memory (and very scarce in quantity),

it is recommended to be reserved for variables that are very frequently accessed.

Tip

Read this to know about global register variables.

Important

register keyword merely reports a suggestion to the compiler; the compiler is within its legal rights to just ignore it if deemed unnecessary.

Note

register variables don't have memory addresses since they are not in memory, so you are prohibited from using the & operator on such variables.

| How to Register Variables | |

|---|---|

1 | |

Inline Functions¶

inline specifier hints the compiler to put the body of a function in its parent scope when it is called; thus avoiding placing data on a new stack frame and retrieving its data. It is merely a hint, the compiler is free to do what is best for actual performance gains.

Tip

Read more about inline functions here.

A static inline function can be declared and defined with no restrictions, but there are restrictions for non-static inline functions. Read the citation in the tip for more information.

Structs, Unions, and Enums¶

A struct is also a collection of data items, except with a struct the data items can have different data types, and the individual fields within the struct are accessed by name instead of an integer index.

Tip

Visit this page for more information.

Tagged Structs¶

struct Part {

int number, on_hand;

char name [ NAME_LEN + 1 ];

double price;

};

Part in the above example, fields being its members. struct Part is now a valid data type.

It is possible to simultaneously declare variables with the following syntax:

struct Student {

int nClasses;

char name [ NAME_LEN + 1 ];

double gpa;

} joe, sue, mary;

Anonymous Structs¶

struct {

int nClasses;

char name [ NAME_LEN + 1 ];

double gpa;

} alice, bill;

struct.

Struct Bit Fields¶

To properly understand the usage of bit fields one needs very low-level knowledge of how computers work, how data-types are stored in memory, etc. However for a general introduction, check this.

Unions¶

Unions are declared, created, and used exactly the same as structs, except for one key difference:

- Structs allocate enough space to store all of the fields in the struct. The first one is stored at the beginning of the struct, the second is stored after that, and so on.

- Unions only allocate enough space to store the largest field listed, and all fields are stored at the same space - the beginnion of the union.

Important

All fields in a union share the same space, which can be used for any listed field but not more than one of them.

In order to know which union field is actually stored, unions are often nested inside of structs, with an enumerated type indicating what is actually stored there.

typedef struct Flight {

enum { PASSENGER, CARGO } type;

union {

int npassengers;

double tonnages;

} cargo;

} Flight;

Flight flights[1000];

flights[42].type = PASSENGER;

flights[42].cargo.npassengers = 150;

flights[20].type = CARGO;

flights[20].cargo.tonnages = 356.78;

Enums¶

Enumerated data types are a special form of integers with the following constraints: - Only certain pre-determined values are allowed. - Each valid value is assigned a name, which is then normally used instead of integer values when working with this data type.

enum suits { CLUBS, HEARTS, SPADES, DIAMONDS, NOTRUMP } trump;

enum suits ew_bid, ns_bid;

typedef enum Direction { NORTH, SOUTH, EAST, WEST } Direction;

Direction next_move = NORTH;

enum Errors {

NONE=0, MINOR1=100, MINOR2, MINOR3,

MAJOR1=1000, MAJOR2, DIVIDE_BY_ZERO=1000

};